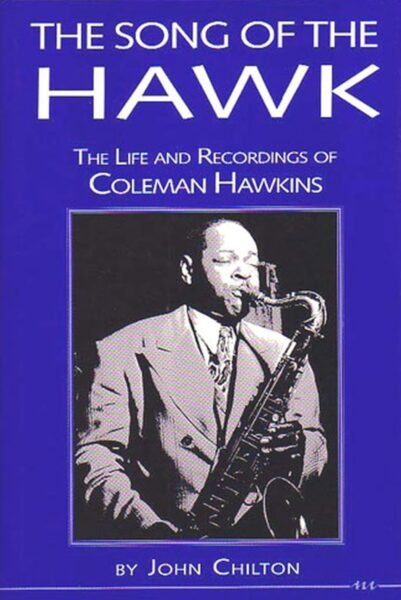

The Song of Hawk – The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins is a biography by John Chilton of Coleman Hawkins, one of the most influential tenor saxophonists and musicians of the twentieth century. John Chilton was an English trumpet player and working jazz musician, who has methodically chronicled every recording session that Coleman Hawkins ever played; this was a lot of sessions. Interspersed with the details of these sessions, are life events, gigs, travels and various quotes from musicians and others that give light to Hawkins and the environment he was living in.

Coleman Hawkins was born in 1904 so most of the recordings were 78s. The book chronicles each of these recordings as a timeline of Hawkins’ life. How Chilton got his hands on these records in unknown and unfortunately the book does not have a discography. The book does gets a bit lugubrious at times with the author’s impressions of the various soloists and recording qualities, but it is for true fans who do not mind the details. For this reader, it was about finding needles in the haystack. Hawkins indeed played and recorded with John Coltrane, Duke Ellington and Thad Jones. These are surely interesting listens that I was unaware of and want to pursue. For many years he took Thelonious Monk under his wing. Many people asked him why he used Monk, who’s playing was unorthodox, when he could have hired a “real” piano player. Hawkins knew genius when he heard it. It is interesting to muse how differently Monk’s career would have been without Hawkins.

While many biographies delve into the personal, The Song of Hawk – The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins, mostly stays away from Hawkins’ personal and family life. The one aspect where this is not true is the insane quantity of liquor consumed. Coleman liked his scotch and brandy.

We just happened to be living in the same hotel in Nottingham, only living about three doors apart. So Fats would bring by my breakfast every morning – a glass of Scotch, full glass, a water glass of whiskey. You see that is the way we drank. It would take me an hour to drink a glass of scotch; he’d drink it in two minutes, straight down, just like he was drinking water. He was a big drinker and a big eater. Yeah, Fats was something else.

Hawkins reflecting on a stint with Fats Waller at a European hotel

We got along nicely. He was such a wonderful person. I couldn’t believe that anyone could drink so much alcohol and that it would have so little effect on him.

Arthur Briggs

But what was amazing about Hawkins was even though he smoked two packs of cigarettes a day and drank all that booze, people generally found him to be a great guy. While he was in many ways a very private person and did not say much, he did often help out younger players and talent.

First, he taught me to put expression into singing ballads, and he did it saying, ‘Carp, if you’re putting a song across, you’ve got to regard it as if you are making love. You greet the song, then you slowly get closer to it, caressing it, kissing it, and finally making love to it, and when you bring your performance to a climax you don’t just end it there and then, you have to be just as tender as you were when you began, so that the audience feels the flow of your expression and they end up peaceful and satisfied.’

Thelma Carpenter

From 1934 to 1939, Hawkins lived in Europe where he played long residencies in various clubs and hotels. Sometimes he was backed up by other Americans but more often by local European players. At one point he took to the slopes.

Hawkins’s success in Switzerland were just as great as those he had enjoyed in other parts of Europe. During the winter of 1935-36 he worked in St Moritz (where he learned how to ski)… his main base was Zurich.

If there is ever a movie made of his life, the film should start with Coleman Hawkins skiing in the Alps, Hawk bundled up, smoking a cigarette, looking out at the sublime mountains, ready to head down the mountain. Needless to say. Mr. Hawkins, while being a fine saxophone player, could also be known as an early predecessor to the modern ski bum. I have a feeling he probably mostly enjoyed the apre ski.

He was amused and sometimes vexed, when local jazz critics praised only black musicians, automatically excluding white performers from any listing of favorites. Having always kept an open mind when listening to jazz musicians, he had difficulty in making Europeans understand that there were some white jazz musicians he genuinely enjoyed. “After all. I played with Benny Goodman and all of them and I didn’t know any clarinet player that played more than Benny.”

In 1939 he returned to the United States. In that same year he recorded the ballad Body and Soul which was a big hit and set the stage for the modernism on 52nd Street – tritone substitutions, irregular measured phrases, harmony derived from the vocabulary of Ravel and other impressionists, complex polyrhythms and ridiculously fast tempos which soon challenged the pop tune and riff-based music of the big band era.

It is always important to note that Coleman Hawkins idea of a good time at home was kicking back and listening to classical music. He had a vast collection of operas and symphonies on vinyl and a state-of-the-art high-fi. People commented that when they visited him in his apartment they would find him in a comfortable chair with an opera playing on the hi-fi and tears streaming down his face.

Competitive to the end, you get a real sense of this with a recollection from Cannonball Adderley.

A young tenor player was complaining to me that Coleman Hawkins made him nervous; I told him Hawkins was suppose to make him nervous for forty years.

Julian “Cannonball” Adderley

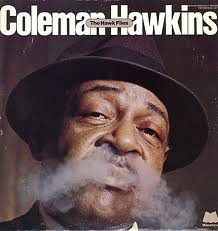

While The Song of Hawk – The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins is a welcome addition to the genre of jazz history, one can get a very good idea of the life of Coleman Hawkins by simply reading the liner notes by Dan Morgenstern of The Hawk Flies which won a Grammy award for liner notes. Morgenstern knew Hawkins well and later in his life helped him get gigs. There was a heartfelt personal relationship there which is non-existent in The Song of Hawk – The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins. The Song of Hawk digs very deep in a very methodical way into the life of Hawkins in a very detached way. I doubt anyone will take the time to write it again. It is a welcome addition to understanding this music called jazz.

While The Song of Hawk – The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins is a welcome addition to the genre of jazz history, one can get a very good idea of the life of Coleman Hawkins by simply reading the liner notes by Dan Morgenstern of The Hawk Flies which won a Grammy award for liner notes. Morgenstern knew Hawkins well and later in his life helped him get gigs. There was a heartfelt personal relationship there which is non-existent in The Song of Hawk – The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins. The Song of Hawk digs very deep in a very methodical way into the life of Hawkins in a very detached way. I doubt anyone will take the time to write it again. It is a welcome addition to understanding this music called jazz.

CODA

When I was fifteen years old, living in Madison, Wisconsin, one summer I went out riding my bike looking for a job. I road down State Street and outside a French restaurant, The Ovens of Brittany, I saw two cooks on break outside. They were hanging out on a stoop, and as people do in the restaurant business, having a smoke break. I asked them if there was any work. After a few moments they asked me if I wanted to clean up and paint the staircase behind them. Somehow a bucket of molasses had been kicked down the stairs. It had splattered everywhere – on the carpeting, against the door, on the walls. We must have agreed on a wage and I then commenced with a bucket of hot water, rags, mop and a sponge. When I had finished later that day, I went to pick up my pay. They were happy with my work and asked what my plans were for the evening. I said that I was free, to which they asked if I wanted to wash dishes. The dishwasher had called in sick. I told them that it sounded great but that I would need to call my mother. And so ensued my decades-long career in the restaurant industry.

The Ovens of Brittany dishroom was in the basement of an old corner building that was probably from the last century. Every ten of fifteen minutes a tub of dishes would make its way down via a manual dumbwaiter. The people who worked at the restaurant were mostly college students, so at a young age I was conversing about adult topics with people five or ten years my senior. From a Jewish guy from New York I learned about the term anti-Semitism. You grew up fast in those days.

With the tips that I made as a dishwasher I would mosey on down to the record stores on State Street and buy vinyl, mostly jazz cut-outs. One of those records was The Hawk Flies a remastered Milestone reissue of various dates. On that record are amazing sidemen – J.J. Johnson, Hank Jones, Nat Adderley, Idrees Sulieman, Max Roach, Thelonious Monk. The sound of Coleman Hawkins and that sophisticated modern music coming out of New York City was the perfect sound track for the feeling I had after a six hour dish shift. I was hooked.